Service Discovery in Kubernetes with Restrictive Permissions

- Most Kubernetes clusters running CoreDNS support reverse DNS lookups by default

- Listing pods and services in a cluster is considered a privileged action, protected by the

listverb on theservicesandnamespaceresources- Bruteforcing the cluster’s IP space via reverse DNS lookups will reveal services available in the cluster

- This allows for some light privilege escalation ™

In a recent red team engagement, I encountered a curious scenario while navigating a Kubernetes cluster. After exploiting a vulnerability in an ephemeral pod and deploying a customized version of the Poseidon agent, I turned to lateral movement and privilege escalation. Generally, I start with the stored API creds already available in the pod located in /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/token to see what I can access.

$ curl -L "https://dl.k8s.io/release/v1.30.2/bin/linux/amd64/kubectl" -o /tmp/kubectl

$ chmod +x /tmp/kubectl

$ /tmp/kubectl --token=$(cat /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/token) auth can-i --list

Resources Non-Resource URLs Resource Names Verbs

selfsubjectreviews.authentication.k8s.io [] [] [create]

selfsubjectaccessreviews.authorization.k8s.io [] [] [create]

selfsubjectrulesreviews.authorization.k8s.io [] [] [create]

[/.well-known/openid-configuration/] [] [get]

[/.well-known/openid-configuration] [] [get]

[/api/*] [] [get]

[/api] [] [get]

[/apis/*] [] [get]

[/apis] [] [get]

[/healthz] [] [get]

[/healthz] [] [get]

[/livez] [] [get]

[/livez] [] [get]

[/openapi/*] [] [get]

[/openapi] [] [get]

[/openid/v1/jwks/] [] [get]

[/openid/v1/jwks] [] [get]

[/readyz] [] [get]

[/readyz] [] [get]

[/version/] [] [get]

[/version/] [] [get]

[/version] [] [get]

[/version] [] [get]

In this case - I couldn’t access anything. This effectively rendered the Kubernetes API useless for further exploration unless I found a new token to try out. I turned to classic old-school lateral movement and host discovery.

I knew a SentinelOne agent was present on the hypervisor so fast network-based host discovery via nmap or zmap would be much too noisy and risk giving away the attacker advantage so early in the engagement. I thought about writing a quick and dirty python scanner with generous sleeping in between hosts, but after discovering I was in a /16 I didn’t have the patience to sit through slowly working by way through 65000 potential live IPs. Additionally, I could identify a live IP but due to how Kubernetes clusters are managed that IP could be reassigned or abandoned at any time if a new deployment or load balancing was performed.

Instead I looked for quieter ways of identifying services and pods that wouldn’t be as scrutinized by security products and audit logs, but allowed me to progress somewhat quickly. I decided to take a look at how CoreDNS worked as there was likely less visibility on DNS queries and resolutions within a cluster.

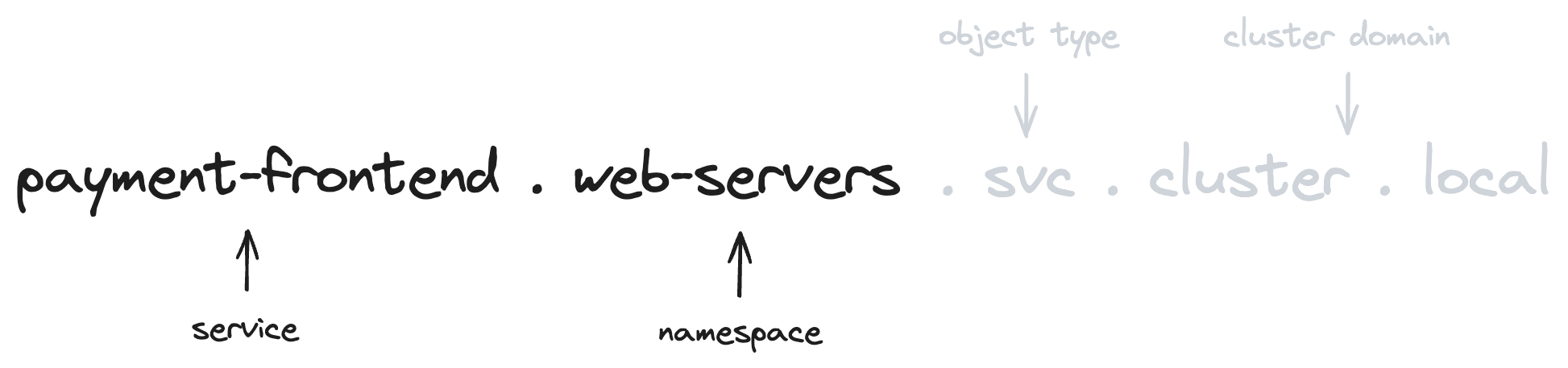

In Kubernetes, DNS is used by pods to identify other services available in the cluster as IPs change frequently. Every service in Kubernetes is provisioned an entry in the cluster’s DNS that corresponds to its service name and the namespace that it’s in:

The only namespace I knew of was the one I was currently in (found in /run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/namespace). I debated generating a wordlist of common namespace and service names but decided against bruteforcing.

From previously listing network interfaces, I knew that I was in a /16 network and could iterate through the IP addresses performing reverse lookups if CoreDNS automatically inserted PRT records or if it resolved the in-addr.arpa domain name.

As it so happens, this is a feature of CoreDNS which is enabled by default. The in-addr.arpa domain being present allows for the server to automatically resolve our reverse lookups.

I wrote a quick and dirty pastable python script that will read an IP range in CIDR notation from the environment and try a reverse resolution for each IP:

import socket

import ipaddress

import os

cidr = os.environ.get('cidr')

net = ipaddress.ip_network(cidr)

for ip in net:

name = socket.getnameinfo((str(ip), 0), 0)[0]

try:

ipaddress.ip_address(name)

except ValueError:

print(f'{name} -> {ip}')

Collapsing this script into a one liner and running it through python looks something like this:

$ cidr="172.20.0.0/16" python3 -c "exec(\"import socket\nimport ipaddress\nimport os\n\ncidr = os.environ.get('cidr')\nnet = ipaddress.ip_network(cidr)\n\nfor ip in net:\n\tname = socket.getnameinfo((str(ip), 0), 0)[0]\n\ttry:\n\t\tipaddress.ip_address(name)\n\texcept ValueError:\n\t\tprint(f'{name} -> {ip}')\")" | grep -v "compute"

I had to grep out the non-service responses or else every IP address would return a default AWS resolution like ip-172-20-0-7.us-east-1.compute.internal.

Letting this script run for a bit gave me a complete list of services in the cluster and their currently associated IP addresses. Additionally, because the namespace a service is hosted in appears in the domain name for it, I get a partial list of valid namespaces in the cluster. This essentially allows an unprivileged token to give itself the list verb on the services and namespaces resources, even if they have been explicitly denied.

Armed with a list of valid services in the network I could now pivot to software identification and port scanning.